Diet

Contents

Introduction

Okay, so you want to lose some weight and/or improve your figure, but you're finding it really hard to do, despite going to the gym and getting on the treadmill for an hour every day and trying to eat healthy. The problem is that none of these things will actually do much to help you achieve your end goal. What, then, is the solution? To find a solution, one must first understand the problem.

The Fundamental Rule

When it comes to fuel, the human body isn't terribly different from a giant incinerator. To operate, we need a certain amount of fuel per day. This is called the Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR)[1] and is based directly on our biology: current weight, current height, current age, and gender. The heavier and taller you are, the higher your BMR. The older you are, the lower your BMR. And, sorry ladies, men have a higher burn rate than women.

In addition to your BMR, your normal daily activity influences your daily calorie requirements. This is known as the Harris-Benedict Coefficient (HBC)[1].

| Activity Level | Coefficient |

|---|---|

| Sedentary (little to no exercise) | 1.2 |

| Light activity (light exercise, or sports 1-3 days/week) | 1.375 |

| Moderate activity (moderate exercise, or sports 3-5 days/week) | 1.55 |

| Very active (hard exercise, or sports 6-7 days/week) | 1.725 |

| Exceptionally active (very hard exercise every day, a physical job, or 2x training) | 1.9 |

To determine your daily calorie requirements, multiply your BMR by your associated HBC. This number is the number of calories you need to eat per day to maintain your current weight. This point brings up the fundamental rule of weight-loss:

Understanding Weight Gain

Armed with the fundamental rule, there are a few additional factors to be aware of about your body. There are three fundamental parts of food: protein, carbohydrates (carbs), and fat. Your body needs all of these, and none of them are bad for you on their own merits. Protein provides the fundamental building blocks your body needs to carry out all its little functions. Carbs provide a readily accessible form of energy (a.k.a. simple sugars) that it can quickly utilize when needed. Fat stores energy for later, when the carbs are depleted.

That last part is important: any time you consume more calories than you burn, your body stores them as fat for later use. That's the key to the fundamental rule: when you eat more calories than you need, it will get stored as fat. Whatever your body won't ever make use of gets excreted as waste.

Waste is an important topic, too. In addition to being a giant incinerator, your body is also a giant water pump. You put water in the top and it comes out the bottom. However, as it does so, it does some very important lubrication and cleansing things. The more water you drink, the better able your body is to process what you put in it and wash out the stuff it doesn't need. If it doesn't have enough water to keep this process moving quickly and efficiently, garbage gets stored as fat, too. This is the key behind the idea of drinking eight cups (or more) of water per day: you need to stay hydrated so your body can engage in its necessary processes.

The Role of Ketosis

The fundamental rule already seems to give away the key to weight loss, but there's a catch. Whenever you eat less than you burn, your body enters into a state called ketosis. The mild version of ketosis is excellent: your body decides that it's starving and so it breaks into its fat reserves to find the energy it needs. The result is that all that padding around your body starts disappearing.

The downside, however, is that your body thinks it's starving! As a result, any food it gets is more likely to be stored, so it can be relied on later. After all, your body doesn't know that it lives in an industrialized society where food is abundant; it still thinks it's on the plains hunting Woolly Mammoths. Fortunately, this behavior is only a problem when you go to more severe forms of ketosis. Mild ketosis, like the kind advocated below, brings you the benefits without the downside. It is, nevertheless, important to be aware of it.

Losing the Weight

Now that you're armed with the basic knowledge of BMR, daily calorie requirements, ketosis, and the fundamental rule, we can start applying these ideas in a practical way.

Cutting Calories

The fundamental rule shows that cutting calories leads us to weight loss. How much so? One pound of fat is equivalent to 3500 food calories. To lose one pound of fat in a week, you would need to cut 500 calories from your daily calorie requirement, with no changes to your daily activity level. Period. You can eat whatever you want — if you want to eat your daily intake requirement in potato chips, you can do that. As long as you're running a deficit, you'll see results (though I don't recommend doing this at all!).

Calorie Accounting

One way to make sure you keep to your target number is to maintain a spreadsheet. This is easy to do in our modern world and has been proven to be very effective at aiding weight loss [2]. Most Windows and Mac computers come with some form of Microsoft Office. If you don't have Microsoft Office, you can download OpenOffice for free. You can also use GoogleDocs to create a spreadsheet. There are specific websites out there focused on calorie counting, with vast databases of food to reference. If all else fails, you can use a piece of paper. There are plenty of options and no excuses!

In one column, write down what you ate. In the next column, write down how many servings you ate. In the next column, the number of calories per serving. This information can usually be found on food labels. Failing that, or if you're dining out, you can locate it on any of several websites focused on helping you count calories. In the final column, put the total number of calories (i.e. how much you ate × the number of calories per serving).

Serving size is an important, but misunderstood concept. One serving of food is not, necessarily, how much you should eat. It's just an arbitrary unit about which the food statistics relay information. Have eight servings of something, if you like; there's nothing wrong with that. Just be aware of what's in those servings.

The following table provides an example of what a person might eat in a given day. I've included a "meal" column to indicate for which meal the food was eaten.

| Meal | Food | Servings | Calories/ Serving |

Total Calories |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breakfast | Egg, sunny-side up | 1 | 90 | 90 |

| Breakfast | Bacon (1 strip per serving) | 4 | 42 | 168 |

| Lunch | Chicken leg, rotisserie-style | 3 | 264 | 792 |

| Dinner | Steak (1 oz. per serving) | 12 | 71 | 852 |

| Dinner | Broccoli, steamed (1 small stalk) | 5 | 49 | 245 |

| Total | 2,147 | |||

This would be a reasonable diet for a sedentary, 30-year old man about 5'10" and weighing 310 pounds.

Important Caveats

500 calories is a pretty good target for most people, but there are two important caveats:

- You should never try to lose more than two pounds per week. Doing so is dangerously unhealthy. You may see results that have you losing more than this, but never ever cut more than 1000 calories from your daily calorie requirements.

- You should never cut your daily calorie intake lower than 1800 (men) or 1200 (women). These are the absolute minimums, and are extremely low in their own right. Going below this, you will not have a sufficient level of nutrients in your body and will experience dizziness, lack of energy, etc.[3]

For some people, particularly women, this is going to make losing weight through calorie-cutting alone difficult or impossible. A 23 year old, sedentary woman weighting 150 lbs. at 5'2" is going to find herself with a 1300 calorie diet if she cuts 500 calories out. This comes very close to the 1200 calorie limit, and she may experience dizziness, lack of energy, headaches, etc. There is, however, a solution.

Exercise the Deficit

Instead of cutting 500 calories to hit your target imbalance, the alternative is to add in some exercise. For some people, this won't be necessary and for others it will be vital. Suppose you can't get by after cutting 500 calories from your daily intake. Instead, cut 300 (or less) and make up the difference by hopping on a treadmill, going for a bike ride, playing a sport, or weight-lifting. Weight-lifting is the best of these options, which is detailed below.

The Importance of Healthy Food

Many diets make a big deal about what you eat. This diet doesn't do that; you can eat whatever you want. However, it's worth pointing out that the reason certain foods are considered healthier stems from two important factors.

- Healthy foods tend to be denser in nutrients per calorie than unhealthy food. Yes, you can get some of the nutrients you need from a potato chip, but you can get a lot more from some spinach.

- Foods made with high-fructose corn syrup don't send the signal that you're full[4].

While the first point is self-explanatory, the second point is one of the major players behind the obesity epidemic suffered by Americans today. Politics aside, our country produces an astonishing amount of corn. As a result, it's cheaper to process corn and make a sweetener called high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) than it is to import or grow regular cane sugar (typically, sucrose). The problem with HFCS is that, unlike regular sugars, it doesn't send the same chemical signal to your stomach to stop eating once full. Consequently, it's very easy to load up on HFCS-laden food, packing on the calories. Counting your calories will help to mitigate this, and it's all but impossible to avoid HFCS in American food, but if you make a modest effort to avoid HFCS (check the label!), you'll begin to find that you feel fuller with less.

Side-note: There are commercials airing on American TV that advocate HFCS is perfectly safe in moderate amounts. This is quite true; HFCS is not harmful on its own. However, the effect HFCS has due to its inhibition of the "fullness" indicator in your stomach, is a key player in the obesity issue. The key to that commercial is the phrase moderate amounts; most Americans don't eat HFCS-rich food in moderate amounts because they are unaware just how much they are eating!

Seeing Progress

For many people, one of the problems with diets that don't promise fast results is the lack of reinforcement. If we don't see changes from day to day, we get disheartened and give up, perhaps binging on ice cream to console ourselves. As such, it's vital to figure out how to see your progress.[2] One way to do this is to measure and chart it.

The Weight Log

We've already discussed the importance of keeping a daily food log when tracking calories. Now we go one step further and add a daily weight log. Many people are afraid of the scale, particularly if they're overweight. This is a fear that must be overcome; you need to know what your weight is in order to know if you're making any progress. No one but you will know, and while the measurements may be distressing at first, being able to see your weight loss happen before your eyes is immensely rewarding.

You will need a basic scale in order to do this, and they are quite inexpensive. All you need is a scale that'll tell you your weight; any additional frills are up to you. You should weigh yourself at a consistent time of day. Conventional wisdom holds that first thing in the morning is the best time, since your stomach will be empty. If you shower in the morning, you should weigh yourself before you shower, lest any water you're retaining from the shower make you appear to weigh more than you really do. You should also weigh yourself naked; your clothes aren't going to lose weight when you diet.

Simply record your weight each day in a seperate spreadsheet. This alone will be useful. However, it will also be misleading from day to day. You may see spikes in your weight from day to day if you just track this value. These will usually be affected by factors like how much water is in your body, how recently you visited the bathroom, and so forth. They are not truly representative of your weight. You need to play with the raw data a bit for that.

Exponentially-Weighted Average Weight

For those of you afraid of math, batten down the hatches. We're going to tackle a concept known as the exponentially weighted average (EWA). You are probably familiar with the arithmetic mean, which most people call the "average." Arithmetic means add all values together, and divide by the number of values. If I have three children, ages 5, 8, and 12, the arithmetic mean of their ages is a little over 8 (5 + 8 + 12 = 25 / 3 = 8.33).

EWAs are different, in that they give preference to the most recent term in a list of terms. In other words, my weight today has the same weight as the weighted average of my weight from the day before. This goes as far back as I want it to. In general, 10 days is a good interval. If I don't have 10 days, I weight the values based on the number I do have.

I realize that this concept will be nebulous to most people when they first run into it; I'm a math nut and it took me a good while to wrap my head around it, too. To demonstrate, here's a sample chart of my own daily weight measurements, including the EWA.

| Day | Weight | EWA | Offset |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 184.8 | 185.7 | -0.9 |

| 2 | 184.5 | 185.5 | -1.0 |

| 3 | 184.2 | 185.3 | -1.1 |

| 4 | 183.9 | 185.0 | -1.1 |

| 5 | 183.7 | 184.8 | -1.1 |

| 6 | 183.4 | 184.5 | -1.1 |

| 7 | 183.1 | 184.3 | -1.2 |

| 8 | 182.8 | 184.0 | -1.2 |

| 9 | 182.8 | 183.8 | -1.0 |

| 10 | 182.8 | 183.6 | -0.8 |

The offset column is the most important one to look at here, which indicates the discrepancy between the measured weight and the EWA. As long as the offset is negative, you are actually pulling down your EWA weight! Although my weight for the last three days measured the same, my EWA was still coming down by a large amount. This static period is nothing to worry about, as long as there's still some movement on the EWA side. Many people will see the scale and be alarmed that they're not losing weight. The EWA chart helps to assuage that concern.

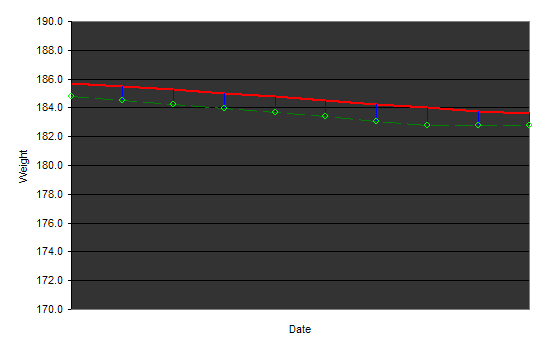

The EWA chart can also be made into a graph, for visual people (like me!).

Because the EWA smooths out data from many days, it paints a much nicer line. Additionally, the offset values can be used to make "floaters and sinkers," to show which values are pulling up the EWA line and which ones are helping it come down.

Plateaus

You may find, as you lose weight, that you hit periods where your weight seems to remain unchanging for a week or more. These are known as weight plateaus, and are perfectly normal. Everyone has different weight plateaus, but they are points at which your body has decided it has hit a happy equilibrium and will contentedly and stubbornly remain there for a while. Just continue with your dieting (and exercise, as needed) as normal and eventually your body will begin shedding pounds once more.

Exercise: Burning Calories and Toning Up

If you've come this far, you're losing weight like a champion, you've got your charts, and you're counting your calories. But something doesn't look quite right. You still feel like you don't look as good as you want to. The reason for this is because of your weight loss. You've just decreased the internal volume of your body by a fair amount, so now you've got a bunch of loose skin with nothing to do. Often, when people complain about this, they complain about having no tone. The reason is that while they have lost fat, they have not gained muscle to replace it.

While many people advocate cardio for exercise and weight loss, they do so from a misinformed point of view. Cardio is great, no question about it. It'll improve your endurance, your blood oxygenation, and will help to boost your daily calorie requirements via the HBC. It will not, however, do so as well as weight lifting. [5]

Why Weight-Lifting is the Key

Cardio is a single-step process: you start moving in a rhythmic way, burn calories as you do so, and then stop. Many people who engage in cardio-based activities look great, too: dancers, gymnasts, runners, etc. However, cardio alone only does about a third as much as weight-lifting can do.

When you lift weights, you're doing three things:

- You're burning calories to lift the weights.

- You're gaining muscle mass, thereby improving your tone by filling out your now-baggy skin with new muscle.

- You're burning calories as you rebuild/build anew the muscle that grows as a result of your weight-lifting.

So, you're burning calories twice, and improving your tone all at the same time. Cardio exercises your muscles, for sure, and as a result will also do a little to improve tone. It will not, however, burn as many calories per unit time invested, nor will it build muscle as well. Your best bet is weight-lifting.

A Simple Weight-Lifting Exercise

Another great thing about weight-lifting is that it requires very little investment to do at a basic level. Milk jugs, filled with varying amounts of water, can serve as reasonable dumbbells (though I advocate going to a gym or buying a set of your own dumbbells if you plan to do this continuously). If you're sedentary, try adding the following weight-lifting routine to three days out of the week. Space the days out so that you have time to recover after each workout. Each workout described should be done (as best as you can) in five sets, with each set comprising five reps (individual lifts). Each successive set should increase the weight by a reasonable amount (say, 5 pounds per arm) up to the limit you can safely lift.

- Basic curl

- Sit on a comfortable seat, legs spread apart, with nothing between them.

- Rest your weight-bearing arm's elbow against the inside of your thigh, arm hanging down.

- Slowly lift the weight in a smooth, arcing motion from your elbow. Do not move your elbow from your thigh!

- Bring the weight to your chin, and then slowly bring it back to the floor.

- Bent-Over Shoulder Row

- With one foot on the floor, put the other leg's knee on a raised surface.

- Lean down until the arm on the same side as the resting leg is also leaning against this surface.

- With the weight in the freely hanging arm, pull the weight to your chest, allowing your elbow to raise above your back as you do so.

- Slowly lower the weight back to the floor.

- Vertical Back Press

- Sit, with a weight in each hand, and your back against some form of support.

- Raises the weights so that they are at shoulder-height, with your elbows pointing toward the floor.

- Push the weights above your head until your arms are almost fully extended

- Slowly bring the weights back to shoulder-height.

I cannot stress enough the importance of having a spotter, particularly when you get to the heavier weights at the end of your sets. Also note that these exercises all stress the arms, chest, and back and will build muscle in those areas. You may also want to do leg lifts or crunches (sit-ups and crunches are identical in terms of abdominal muscle-building) to build muscle in other areas. As a small concession to cardio, jogging and biking tend to be excellent ways to build leg muscle.

The Backslide Fallacy

Some people have argued that weight-lifting is not a good choice because of the risk of back-slide. That is, if you stop weight lifting, you will lose the muscle and tone you gained over time, until you revert to a "natural" level. This is a half-truth. While it is true that if you stop working our muscles, they will lose the no-longer-necessary muscle mass they have built up, this remains true for any other form of exercise as well! If you stop exercising altogether, your muscles begin to experience atrophy, in which they begin to shrink due to disuse. Your body doesn't see the need for them, and so doesn't spare the energy required to maintain them.

No matter what kind of exercise you do, this will hold true. If you pick up a sport as a means of exercising, lose the weight/get the figure you want, and then stop playing, you'll experience some amount of backslide here, too! The key is to raise your overall activity level in life and then maintain it. This holds true no matter what exercise you engage in.

The Bulky Fallacy

Many women (moreso than men, at least) balk at weight-lifting because they do not want to bulk up. Given the prevailing concepts of beauty and the physique of many female body builders, I absolutely understand where they're coming from. However, this concern is unwarranted. Lifting weights, in its own right, will not cause you to bulk up. It will only improve your tone and increase your strength.

In order to bulk up, your body needs an influx of building material from which to work, namely protein. You also need to eat a lot more than your daily requirements, not less, to provide the necessary excess for your body to kick into overdrive. You also need to exercise enough to utilize all of this extra material. Bulking up is hard. Actors provide great evidence of this: they spend months of intensive physical training just to gain 10-15 pounds of muscle for a role, and often have to engage in bizarre, protein-rich diets to do so.

Bottom-line: you will not bulk-up from weight lifting unless you intend to.

Summary of Formulae

- BMR (lbs. = weight in pounds, in. = height in inches, age = age in year

- Women: 655 + ( 4.35 × lbs. ) + ( 4.7 × in. ) - ( 4.7 × age )

- Men: 66 + ( 6.23 × lbs. ) + ( 12.7 × in. ) - ( 6.8 × age)

- Ex: 66 + (6.23 × 184.8) + (12.7 × 70.5) - (6.8 × 25) = 1944

- Harris-Benedict Coefficient: A multiplier for BMR based on daily activity to determine Daily Calorie Requirements

- Sedentary: 1.2 (little to no exercise)

- Light activity: 1.375 (light exercise, sports 1-3 days/week)

- Moderate activity: 1.55 (moderate exercise, sports 3-5 days/week)

- Very active: 1.725 (hard exercise, sports 6-7 days/week)

- Extra active: 1.9 (very hard exercise, physical job, or 2x training)

- Daily Calorie Need: BMR × HBC

- Exponentially-weighted average weight (EWA = exponentially-weighted average weight, Period = number of days to use in the weighting)

- (Today's Weight - Yesterday's EWA) × (2 / (1 + Period)) + Yesterday's EWA

- If yesterday's EWA is unavailable (i.e. you're just starting), use Today's Weight in both

- Ex: (181.4 - 182.5) × (2 / (1+10)) + 182.5 = 182.3

- In this example, the person is on-track, since their actual scale weight (181.4) is below their EWA weight for the day (182.3).

- Usually, 10 is a good Period to use. If you don't have 10 "entries," (i.e. you're just starting out) decrease this number to the number of prior measurements you have. Be aware that this will artificially give extra importance to the measurements on these days.

- (Today's Weight - Yesterday's EWA) × (2 / (1 + Period)) + Yesterday's EWA

Sources

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 A Biometric Study of Human Basal Metabolism. Harris, J. Arthur and Benedict, Francis. 1918.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Using food diaries doubles weight loss, study shows. USA Today. 2008 Jul 07.

- ↑ Calorie Intake to Lose Weight. BMI Calculator.

- ↑ "Supersize Me" Mice Research Offers Grim Warning for America's Fast Food Consumers. Dixon, Rachael. 2007 May 24.

- ↑ Weight lifting, not cardio training, the key to weight loss, according to local trainer. Theiss, Evelyn. 2008 Feb 26.

See Also

- The Hacker Diet provided a lot of the seed information that fueled this article, including the EWA charts.